I was privileged to join clergy from the Moravian Church, Northern Province, on a Pilgrimage toward Racial Justice and Healing September 13-16. I'm grateful to the Moravians for welcoming me. Their reputation for hospitality is not widely known but so well earned. And I want to acknowledge Lancaster Theological Seminary for supporting my participation.

In this post I'll get around to summarizing key points of the trip, but I think it's more important to share my own learning.

The tour made more acute my need for spiritual growth. We White people can

get weird around race, and I'm no exception. I'm no expert, but I know a fair amount about the basics of slavery, Jim Crow, migrations, and the Civil Rights Movement--less about mass incarceration. On too many

occasions I've been confronted with my own desire to be someone who

"knows" about race and racism, someone who gets it. As I experienced the trip, I realized that my sense of "knowing" is part of my White defense mechanism armor. If I can posture as knowing, maybe people will think I'm committed to justice. Maybe I won't come off as ignorant. Maybe I won't feel uncomfortable. Maybe... something.

I began to pray, as I am every morning still, to be a listener and a learner, not an evaluator. To pause my mind enough for my heart to catch up. I ask this of our seminarians who participate in learning opportunities like the Samuel DeWitt Proctor Conference: let's talk about what you saw and experienced, not so much what you liked or whether you agree or disagree. Let's be responders to the word, not thinkers only (James 1:22).

So I needed to retrace some old steps.Our first day I took a long walk around the center of Montgomery. I was still all in my head, so I repeated the walk early the next morning. I was born and grew up in Alabama, but I have very little experience with Montgomery. I recall only one trip specifically to Montgomery. My high school sent me to a youth leadership conference after my sophomore year. The one outing I remember was to the Montgomery State Capitol, where we stopped on this spot. Here Jefferson Davis took his oath of office as president of the Confederacy. The Daughters of the Confederacy made sure to commemorate the spot. This is what they wanted us to see around 1980.

I vaguely remember that the Capitol looks down on Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Martin Luther King Jr was the new pastor during the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Sure enough, not only does the star on the Capitol steps look down on Dexter Avenue, a statue of Davis sits on the hill too. Still. Here's the view in both directions, though the elevation differential is hard to capture with a camera. The footsteps are right in front of the church, representing the end of the March from Selma.

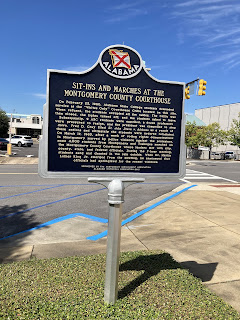

That Wednesday morning walk showed that Montgomery is filled with historical markers to its haunted history. Markers address the slave trade, the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, and the Civil Rights Movement.

Hank Williams too. There's a a little museum.

I began to wonder. Clearly Montgomery makes money off of its racist past. Given Alabama's brutally racist politics today--just watch political ads, you'll see--I wonder about motives. But I also know lots of people live in Montgomery and have influence there. Not just a lot of Black people but also some Whites of good will and some Whites who think they have good will. I just wonder what it means to market this history. History is complicated, and so are people. I'm glad the memorials and museums are there.

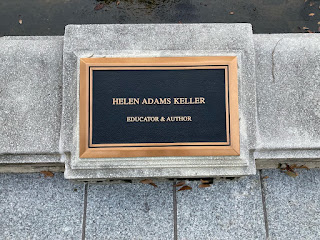

I encountered an oddity. Outside the Alabama Education Association building, offices of the state teachers' union, is a memorial pool dedicated to Alabama's educators. It was dry. I photographed a few plaques that resided side by side. Here they are in sequence.

King. von Braun. Keller. Carver. Wait a minute... von Braun was a Nazi! In school we learned how the United States had brought over von Braun and other Nazi scientists to develop our space program. He worked in Huntsville, where the Von Braun Center is, or was in my day, the major venue for concerts and similar events. I read a biography! I've heard that von Braun's life is complicated, so I'll move on. History is messy, and so are people. I hope he served the Nazis only under compulsion. I hope he resisted. I hope he changed. Whatever. It's just odd to find his name among these legitimate heroes.

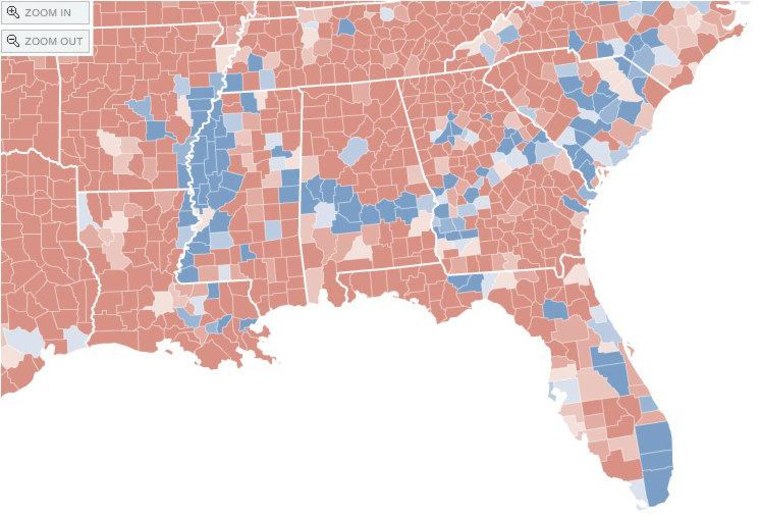

On our first evening our hosts gave us little packets of Montgomery dirt, an experience that began to open my heart to the fullness of things. The dirt is a very dark brown. When I was in school, we all learned about Alabama's southern Black Belt: black because the dirt is black, and black because the population is heavily Black too. Black dirt was good for cotton farming, and slavery made cotton farmers rich.

This is what the Southern Black Belt looks like in racial politics: Blue for counties that vote Democrat. (Source.) See the blue? That's the Black Belt plus the Mississippi River valley.

I grew up in Florence, Alabama. My home county, Lauderdale, is in the absolute northwest corner. The dirt where I come from is not black, it is red clay. For most of my life, I grew up thinking we in North Alabama were "better" when it came to race because all the big Civil Rights news I knew came from Birmingham and further South. Only a few years ago I stopped to look up the percentage of Lauderdale County's population that was enslaved prior to the Civil War: not much different. But I had operated out of the assumption that my people were somehow less complicit, a little more sophisticated. That little packet of black dirt struck home.

Later in the trip we visited to the Equal Justice Initiative's National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which largely commemorates the lynchings that have been documented throughout the United States, especially concentrated in the South. The project has invited teams to collect soil from all those documented sites, and it represents them in glass jars labeled by county. Look at the varieties of dirt.

The Memorial was one of our final stops, and it is a profound experience. Each county where lynchings have been documented receives its own coffin-size pillar with the names and dates of victims engraved. Some rise from the floor. As you walk through, others hang from a high ceiling like bodies from a tree. Copies lie flat on the ground. I determined to find "my counties," especially Lauderdale and Colbert (home to my parents and grandparents), along with Shelby and Davidson counties in Tennessee (where I'd gone to school and taught), York County in South Carolina, and Pennsylvania (included among multiple states). Three documented lynchings in Lauderdale County, twelve in Colbert, and so on.

The experience somehow reminded me that I knew of two lynching adjacent stories as a child but had never framed them that way. Upon reflection, remarkable it is that White children of my generation knew such things but without coming to terms with them at all.

My Uncle Norman related a story from when he was about 10. That would be 1919 or so. He was walking around Leighton, Alabama with the sheriff when a black man rode into town, too well dressed and on too nice a wagon. The sheriff challenged the man and demanded identification. When the man reached into his pocket, presumably for papers, the sheriff emptied his revolver into the man's body. He later took my uncle to inspect the evidence of his good shooting.

It's a story I share rarely because it is so traumatic. But I don't remember trauma or outrage coming from my Uncle Norman, who was not overtly racist. I don't want to evaluate him: yes, his racism came through, but so did his attempts to overcome racism. He clearly told the story as something he'd witnessed that was wrong, evidence of the bad old days. But... he was 10 years old back then, and he later related the story as just something that happened. If I could ask him now....

I also checked out Thirteen Alabama Ghosts from the school library, the kind of book fifth graders just gobble up. It has the story of "The Face in the Courthouse Window." The legend is probably inaccurate, but it's based on a Black man who was killed by lightning inside the Carroll County courthouse as he awaited his lynching. I visited the site as a child! I only learned this in writing this account, but they still perform a drama about it every year in Pickens, Alabama. And it is in children's books.

I am overcome with sadness as I rehearse this to myself. What we learned as children. What we didn't learn. What we didn't feel.

Our first evening in Montgomery featured a presentation by the Rev. Dr. Frank Crouch, who has retired as Moravian Seminary's professor of New Testament and dean. Frank has been poring through Moravian archives, especially in Pennsylvania and North Carolina, in order to come to terms with the church's race history. He's discovered some hard things. Nicholas Zinzendorf himself, one of the great figures in Moravian history, endorsed slavery as biblical, God's punishment upon Black people. The Bethlehem (Pennsylvania) community purchased enslaved people as early as 1742. The Salem community in North Carolina did likewise, where over 200 graves of enslaved persons have been uncovered. Mary Prince, enslaved by Moravians in the West Indies, later narrated her story, published as The History of Mary Prince. She declared that "Slavery hardens White people's hearts toward the Blacks," and that "All slaves want to be free." Frank further documented Moravians' complicity with segregation and shared the story of Charles Martin, the first ordained Black Moravian pastor in the United States who served in New York from 1908-1942. Martin emerged as a civil rights leader in the city, co-leading a 1917 Negro Silent Protest Parade that gathered thousands of participants.

Wednesday revolved around an educational session with Dr. Catherine Meeks, Executive Director of the Absalom Jones Center for Racial Healing in Atlanta. The racial healing terminology is important to her because racism, like all diseases, requires daily attention. Dr. Meeks also asked pressing questions. For example, do we extend the same sympathy to all people, to include those who are homeless or incarcerated? Do we who are White recognize that we too have been wounded by racism? Do we truly desire to live in a world where everyone is free? Questions like these call us to take on real inner work.

Thursday we visited the Rosa Parks Museum, operated by Troy University, which tells the story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. That year is often cited as the unofficial beginning of the Civil Rights Movement. Facing terrific resistance, including losing their jobs and enduring bombings and other instances of violence, Black people in Montgomery walked to work or carpooled rather than take the bus for over a year. Whatever the weather. I had heard stories about White allies. And however this looks to you as a reader, I needed to connect with their stories somehow. Long ago I learned that White allies are never perfect, but I was moved in particular to be reminded of Robert Graetz, a White pastor of a Black Lutheran congregation who had his house bombed because he supported the boycott.

On the same day we visited the Rosa Parks Museum and the Memorial for Peace and Justice, we toured the Equal Justice Initiative's Legacy Museum, which chronicles Black history through slavery and the slave trade through Reconstruction, Jim Crow, lynchings, the Civil Rights Movement, and mass incarceration. I cannot recommend this museum enough. It combines multimedia art, places viewers in the middle of the experience from time to time, and combines video presentations with thick narrative. Take a look at the web site. I could have spent at least five hours there.